Mon 29 December 2025

Every so often, you bump into an Android flag that feels a bit like magic. FLAG_SECURE is one of those. Turn it on and suddenly your app becomes “unscreenshot‑able”: the usual button combo stops working, screen recordings go mysteriously black, and your UI vanishes from the recent‑apps preview. It looks like some kind of hardcore DRM switch.

It’s not. Under the hood, FLAG_SECURE is actually very simple: it’s a way of telling Android, “this specific window is sensitive; do not let its pixels be captured.” That’s it. No encryption, no secret handshakes, just a strong hint to the system about how to treat that window when somebody tries to grab what’s on screen.

In this article, we’ll walk through what FLAG_SECURE does in practice, how it works conceptually, how to use it in code, where it makes sense to turn it on, some patterns for using it without annoying your users, and the limitations you absolutely should not ignore.

1. What FLAG_SECURE Actually Does

Let’s start with what people actually see when this thing is enabled, because that’s usually where the questions begin.

When you set FLAG_SECURE on a window (for example, in an Activity), Android stops treating that window like a normal capture friendly UI and instead marks it as “hands off” for anything that wants pixels.

The first side effect you’ll notice is that screenshots are blocked. The usual system shortcut (for example, power + volume down) either refuses to take a screenshot or produces an image that’s completely black or blank while your secure window is in the foreground. From the user’s point of view, it just looks like the device won’t screenshot that screen. Underneath, Android is faithfully following the rule: the window is marked secure, so the pixels don’t leave.

It’s not only the built‑in screenshot feature that gets shut down. Most third‑party screenshot apps are in the same boat. They also rely on system‑level mechanisms to capture what’s on screen, and when they ask for the pixels belonging to a secure window, the platform hands them a whole lot of nothing. The result is typically the same: a black or blank image, or a straight‑up failure. But keep in mind that using another camera to take a picture of the screen still works.

Move on to screen recording, and the story is similar. Screen recorders typically show a black area instead of your app’s content where the secure window is displayed. You still get a video, but anywhere your secure window appears in the frame, there’s just a dark rectangle. Some recorders might still show system UI or other non‑secure windows around the edges, but your window stays hidden. It’s like cutting a hole in the recording exactly where your sensitive content lives.

Then there’s the recent‑apps / Overview screen, the one you get when you swipe up or tap the Recents button. Normally, Android takes a snapshot of your app’s UI and uses that as the little card preview. With FLAG_SECURE in play, that snapshot is deliberately useless. In the system’s Overview / Recent apps screen, Android won’t show an image of your secure window. Usually, it appears as a plain color or black rectangle, preventing sensitive info from being visible when the app is in the background or when someone is flicking through open apps over your shoulder.

And this is all scoped very deliberately. FLAG_SECURE does not lock the entire device or affect all apps. It only applies to the specific window (Activity, Dialog, etc.) where it is set. If you don’t set the flag on another Activity, that other screen behaves like normal: screenshots work, recordings work, the recent‑apps preview looks like the UI.

In short, FLAG_SECURE protects what the user (or another app) can capture visually from your app via Android’s own display pipeline, but it does so on a per‑window basis rather than as a global “privacy mode”.

2. How FLAG_SECURE Works Under the Hood

Now that we’ve covered the visible behaviour, let’s talk about what’s actually going on conceptually.

The easiest way to think about this flag is as a privacy switch on a window:

- Switch ON → Android is told: “never let this window’s pixels leave the secure display pipeline in a capture‑able form.”

- Switch OFF → The window behaves like a normal one; screenshots and recordings are allowed.

Under the hood, when a window has FLAG_SECURE set, Android’s compositor keeps track of the fact that this window is “secure”. Every time the system is asked to capture the screen—whether through the screenshot API, screen recording, generating the recent‑tasks thumbnail, or in some casting/mirroring scenarios—it has to build an image out of all the visible windows. For windows that are not secure, it happily copies their pixels into the capture. For windows that are secure, any attempt to capture the screen either excludes the secure window or replaces it with a black/blank placeholder.

The important part is that this is enforced by the system, not by your app logic. You don’t have to intercept screenshot events or try to guess when a recorder is running. Once the flag is set, Android itself becomes responsible for making sure that window’s pixels do not leak into screenshots, recordings, or thumbnails. Other apps that try to be clever and use official APIs to capture the display are still bound by the same rules; they ask for pixels, the compositor applies the secure policy, and your content doesn’t show up.

This is also why FLAG_SECURE is reasonably robust against casual or even moderately determined attempts to capture your UI via software. But it’s crucial to keep in mind what it doesn’t cover: it only controls visual capture through Android’s rendering pipeline. It doesn’t magically protect your data in storage, on the network, or anywhere else.

3. How to Use FLAG_SECURE in Code

The implementation side is the easy part. There’s no secret API, no special permissions—just a flag on the window.

You typically enable it in an Activity during onCreate, before or around the time you call setContentView. In Java, it looks like this:

How to use FLAG_SECURE in Java:

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.view.WindowManager;

import androidx.appcompat.app.AppCompatActivity;

public class SecureActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

getWindow().setFlags(

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE,

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE

);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_secure);

}

}

How to use FLAG_SECURE in Kotlin:

import android.os.Bundle

import android.view.WindowManager

import androidx.appcompat.app.AppCompatActivity

class SecureActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState)

window.setFlags(

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE,

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE

)

setContentView(R.layout.activity_secure)

}

}

That’s all it takes to make that Activity’s window secure for as long as it’s alive.

Sometimes, though, you don’t want the window to be secure all the time. Maybe part of the screen is sensitive and part of it isn’t, or maybe there’s a particular mode where you want to allow screenshots. In those cases, you can remove FLAG_SECURE at runtime when it’s no longer needed:

How to remove FLAG_SECURE at runtime when it’s no longer needed in Kotlin:

window.clearFlags(WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE)

How to remove FLAG_SECURE at runtime when it’s no longer needed in Java:

getWindow().clearFlags(WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE);

A key detail here is that FLAG_SECURE is per‑window, not per‑app. The constant is:

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE

There is no manifest setting that automatically applies this to your whole app. You must set (or clear) it per window:

- Each

Activitythat you want to protect. - Each

Dialogor custom window that should be secure.

That’s both a feature and a footgun: you get fine‑grained control, but you also have to make sure every sensitive surface is covered.

4. Common Use Cases for FLAG_SECURE

So where does this make sense in the real world? The short answer is: anywhere you show information that you really don’t want casually sitting in someone’s screenshot archive, cloud backup, or chat history.

Let’s walk through some common categories.

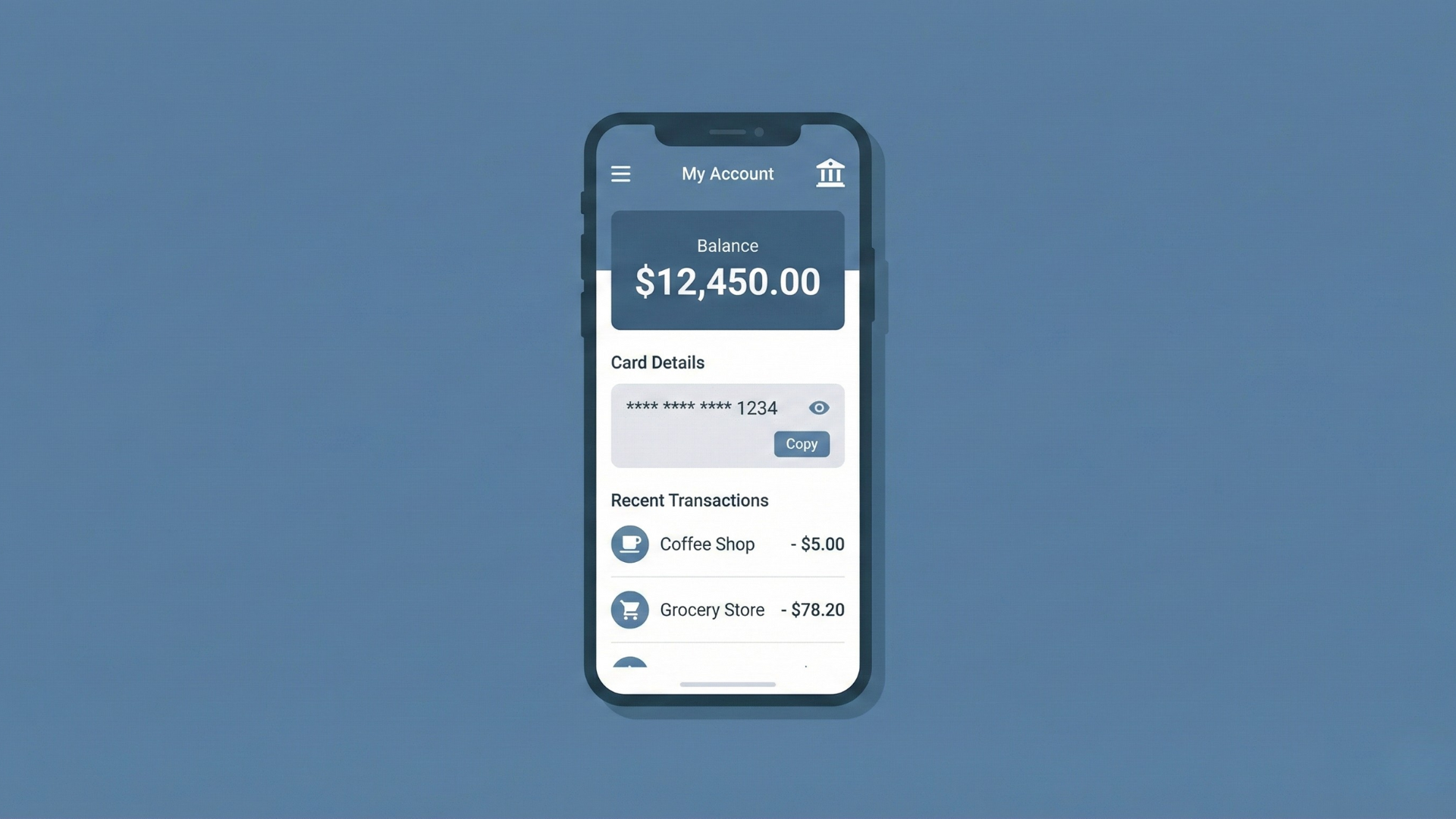

4.1 Banking and Financial Applications

Banking and financial apps are the obvious poster children here. Screens that show account balances, bank statements, transaction histories, card numbers, or one‑time passwords (OTPs) are loaded with data that’s both sensitive and highly reusable if it falls into the wrong hands. If those views happily allow screenshots, that info can end up in the user’s photo gallery, synced to cloud storage, or forwarded in a messaging app, usually with zero encryption or access control.

By enabling FLAG_SECURE on these financial screens, you’re putting a basic speed bump in front of that leakage path. It doesn’t stop someone determined to photograph the screen with another device, but it does prevent a lot of casual, “I’ll just grab a quick screenshot of this” moments that later come back to haunt people.

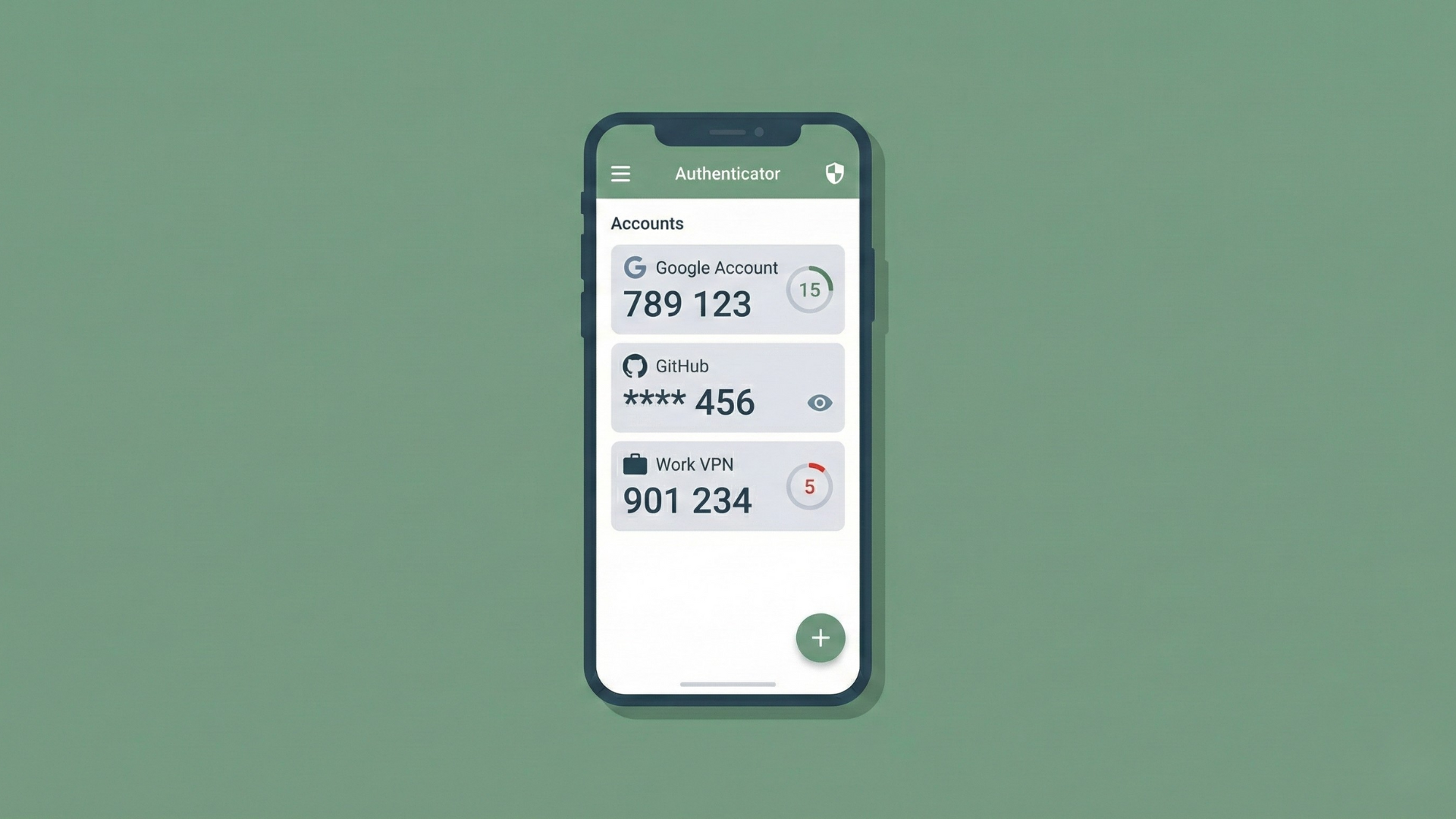

4.2 Authentication and Security Applications

If you’re building anything to do with authentication or secrets—password managers, 2FA / OTP generators, identity verification flows—FLAG_SECURE should be firmly on your radar.

These apps routinely show high‑value secrets: passwords, recovery keys, backup codes, short‑lived login codes, and so on. If users can screenshot those screens, they tend to end up stored in exactly the places you don’t want them: camera rolls, cloud galleries, and random note‑taking apps. From there, it doesn’t take much for them to leak further.

Applying FLAG_SECURE to the parts of your app that reveal these secrets means they can’t be trivially captured via the OS. Users have to take a more deliberate step—like writing them down or using another camera—if they want to persist them. That doesn’t solve every problem, but it dramatically cuts down on the accidental exposure you see when screenshots are allowed everywhere.

4.3 Health and Medical Applications

Health and medical apps sit in a special category where the data is incredibly personal and, in many jurisdictions, tightly regulated.

Screens that show personal health records, lab test results, diagnoses, treatment details, or detailed consultation notes are not just “sort of private”; they’re often subject to strict privacy laws. If those views can be captured as screenshots or video and then automatically backed up or shared, you’ve created an easy path for very sensitive data to leave your app’s control.

Using FLAG_SECURE on these views helps reduce that risk. It doesn’t replace proper encryption, access controls, and compliance work, but it addresses a very concrete issue: people taking a quick screenshot of their results and unknowingly pushing those images into environments that were never designed for medical privacy.

4.4 Enterprise and Internal Tools

Inside organizations, you’ll often find internal dashboards, admin panels, and debugging tools that expose all sorts of information nobody wants on Twitter. Think: internal metrics, customer data, incident timelines, configuration screens, or log views with identifiers and secrets sprinkled through them.

In these environments, employees taking screenshots and sharing them internally might be perfectly normal—until one of those screenshots leaks outside the organization or shows up in a place it absolutely shouldn’t be. Debugging tools used against production systems are especially risky, because they often show raw data that was never meant to be customer‑facing at all.

Enabling FLAG_SECURE on particularly sensitive admin screens and internal tools is a pragmatic way to limit the blast radius of that kind of behaviour. People can still document what they’re doing, but you’re no longer making it effortless to capture and distribute exact pixel‑perfect copies of your most sensitive internal UIs.

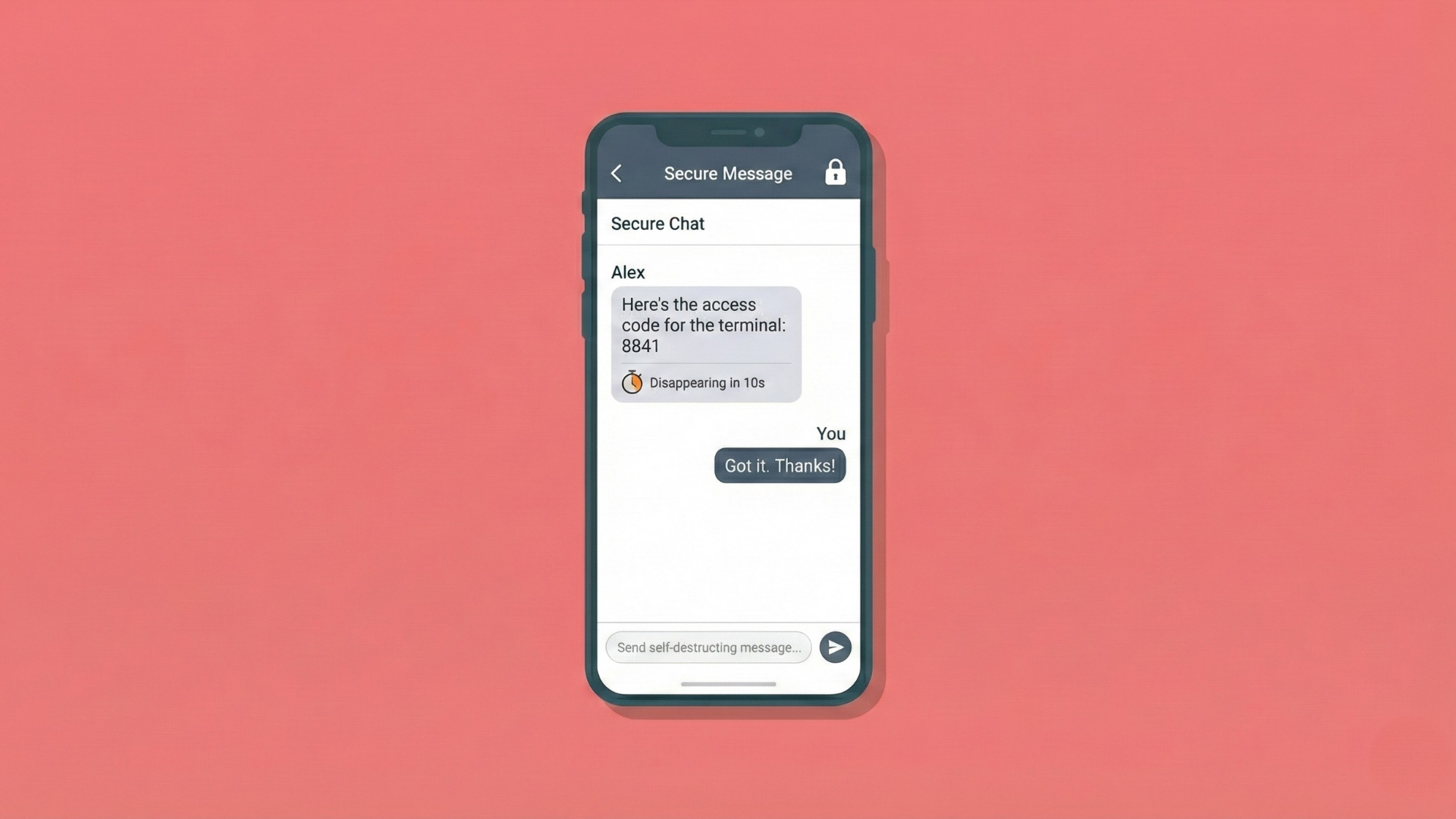

4.5 Privacy‑Critical Communication and Kiosk Scenarios

There’s also a whole class of apps where the sensitivity is more about how people use them than the specific domain. Secure messaging, ephemeral chats, and self‑destructing messages are good examples.

If you’re advertising that “this message disappears,” but the UI is trivially screenshot‑able, the experience and the expectation are misaligned. You can’t stop someone pointing another phone at the screen, but you can at least avoid endorsing the easy, built‑in capture path. Marking those special conversations with FLAG_SECURE sends a pretty clear signal: this is not meant to live forever in your photo gallery.

Kiosk‑style applications are another interesting case. Think of check‑in terminals, queue systems, self‑service forms, or any shared device that people walk up to and use in semi‑public spaces. Often, those screens will briefly display names, IDs, booking details, or other personal data. By enabling FLAG_SECURE on those flows, you make it much harder for opportunistic users—or malicious software running on the device—to quietly harvest what’s shown on the screen.

FLAG_SECURE where the sensitivity of what’s on screen clearly outweighs the convenience of screenshots. Everywhere else, think twice before switching it on.

5. Design Patterns: Where and When to Enable

Just randomly sprinkling FLAG_SECURE around your app isn’t a strategy. You want deliberate patterns that balance security and usability.

One simple pattern is the “always secure” Activity. For certain screens, everything they ever show is sensitive. Classic examples are something like OtpVerificationActivity or CardDetailsActivity. In those, you can just set FLAG_SECURE in onCreate and never clear it. Any time the user lands on that Activity, screenshots and recordings are out of the question, full stop.

A more nuanced pattern is the state‑based toggle. Imagine a single MainActivity that normally shows harmless content, but sometimes reveals a “Sensitive Details” panel—a bottom sheet with full account numbers, for example. While that panel is hidden, there’s no reason to block screenshots. As soon as you show it, you flip the flag on; when it’s dismissed, you turn the flag off again. In Kotlin, that might look like this:

fun showSensitiveContent() {

window.setFlags(

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE,

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE

)

// Show a fragment or view containing sensitive data

}

fun hideSensitiveContent() {

window.clearFlags(WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE)

// Hide that fragment or view

}

That pattern gives you the best of both worlds: people can still screenshot the generic UI, but the truly sensitive moments are protected.

Then there’s the dialog‑only secure content approach. Sometimes, the only sensitive part of the whole flow is a transient dialog—say a pop‑up revealing a full card number, a recovery phrase, or a one‑time secret. In those cases, it can make sense to set FLAG_SECURE on the dialog’s own window instead of the entire Activity. The base screen stays screenshot‑friendly, but the dialog content never shows up in captures.

Whichever pattern you choose, the key is to be consistent: define which screens or states are considered sensitive, apply FLAG_SECURE there, and leave everything else alone. That way, you’re not randomly surprising users, and you’re targeting the flag exactly where it buys you the most risk reduction.

6. Limitations and Misconceptions

Now for the part that’s just as important as the features: what FLAG_SECURE doesn’t do.

The big one: it does not block cameras or external devices. A user can still point another phone, a DSLR, a webcam, or whatever they like at the screen and capture it. FLAG_SECURE only controls software‑based capture inside Android. If your threat model includes someone physically standing there taking photos of the device, this flag doesn’t help you.

Next, FLAG_SECURE does not encrypt or otherwise secure your data. It protects the visual display, not:

- Network communication

- Storage on disk

- Logs, caches, or backups

If you’re sending sensitive data over the network, you still need HTTPS (and you still need to validate certificates correctly). If you’re storing secrets on disk, you still need encryption mechanisms like encrypted databases or EncryptedSharedPreferences. If you’re logging sensitive values, FLAG_SECURE won’t save you when those logs are shipped off to a central server.

There’s also the scope problem. Because the flag is per‑window, not global, it’s very easy to secure one path and forget another. If your sensitive data can also be reached in another Activity or view that doesn’t set FLAG_SECURE, that other screen can still be captured. You need to think in terms of “every place this information appears” rather than “this one screen”.

Another subtle point: FLAG_SECURE does not retroactively protect old captures. Screenshots or recordings taken before you enabled the flag are not affected. They stay wherever the user stored them—local gallery, cloud backup, messaging app. The flag only applies to capture attempts while it is active.

Finally, there are user experience trade‑offs. Some users rely heavily on screenshots to report bugs, save instructions, or document workflows. When you block screenshots in places they don’t perceive as particularly sensitive, you’re going to frustrate them. Overuse of FLAG_SECURE may leave people feeling like your app is unnecessarily locked down, especially if you don’t clearly communicate why a screenshot isn’t allowed.

The takeaway: FLAG_SECURE is a focused tool that addresses one specific problem very well. It is not a silver bullet. You still need real security design around it.

7. Interactions with Casting and External Displays

One last wrinkle that often surprises people: how FLAG_SECURE behaves when you’re casting or mirroring the screen.

Depending on the Android version and the device, content marked with FLAG_SECURE may not appear at all on certain external displays. If the system considers the external display “non‑secure” (for example, some cast targets or mirrored displays), it applies essentially the same logic it does for screenshots and recordings.

In practice, this means that during screen mirroring or casting sessions:

- Secure windows may show up as a blank or black area on the remote display.

- Non‑secure UI and system chrome may still be visible.

- Your app might look like it’s “missing” parts of its UI on the casted output whenever a secure window is in front.

This behaviour lines up with the wording you’ll sometimes see in the documentation: “Prevents the content of the window from appearing in screenshots or from being viewed on non‑secure displays.” “Non‑secure displays” here is shorthand for outputs Android doesn’t fully trust to enforce the same guarantees it can on the device’s primary screen.

If your app is used a lot in presentations, demos, or remote support scenarios, it’s worth testing how your secure screens behave under casting and deciding whether that’s acceptable. In some cases, you might need alternate flows for those situations or at least a friendly message explaining why the screen can’t be shared.

8. Summary

FLAG_SECURE (WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE) is an Android window flag that says, “don’t let this window’s pixels be captured.” Once set on a window, it stops standard screenshots from working, causes screen recordings to show black where that window appears, hides meaningful thumbnails in the recent‑apps view, and can even prevent content from showing up on certain external displays.

You use it by setting the flag on the windows that matter—typically specific Activities or Dialogs—and, if necessary, clearing it again when the UI is no longer showing sensitive data:

window.setFlags(

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE,

WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE

)

// Later, if needed:

window.clearFlags(WindowManager.LayoutParams.FLAG_SECURE)

You should consider it on screens that show genuinely sensitive or regulated information: banking details, authentication secrets, health data, internal dashboards, privacy‑critical chats, kiosk flows, and similar cases. But you also need to be very clear about what it doesn’t do: it doesn’t stop cameras, doesn’t encrypt anything, doesn’t apply globally unless you make it, and doesn’t clean up past screenshots.

Used thoughtfully, FLAG_SECURE is a very handy way to close off one specific, very common leak: pixels leaving your app via screenshots and screen recordings. It’s not the whole story of security on Android—but for the right screens, it’s a story you absolutely want to be telling.